At the mention of Groote Schuur in Cape Town, most people immediately think of the hospital. Yet Groote Schuur is also the house that belonged to Cecil John Rhodes and which he bequeathed it to the nation - along with vast tracts of mountainside that stretched all the way to Constantia Nek, Kirstenbosch included.

Originally, Groote Schuur (Dutch for 'Big Barn') was built by the Dutch East India Company in about 1657 as part of De Schuur, the company's granary. By the time Rhodes bought it in 1893, Groote Schuur was in a state of neglect.

By chance he met an untried young English architect who was visiting Cape Town, and commissioned him to restore Groote Schuur. For the architect, Herbert Baker, this was a heaven-sent opportunity to make his name. Rhodes's brief to Baker was to enlarge the house and restore something of its original Cape Dutch appearance.

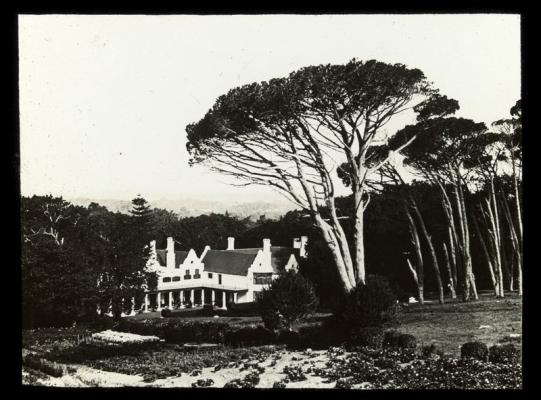

The plan that finally emerged from Baker's drawing board was a charming hybrid of ornate gables, colonnaded verandas, barley-sugar chimneys, whitewashed walls and warm teak woodwork.

Groote Schuur was a triumph for Baker who, with this design, actually created a new form of South African vernacular architecture.

Rhodes had agents and minions on the lookout for furniture, books, porcelain, silver and glassware - he had definite ideas and more than enough money to realise them. He particularly wanted items from the Cape, and many of these had to be reimported from Holland. Today, the house and its interior remain almost exclusively as they were in Rhodes's day.

The rooms have a comfortable domesticity, enlivened by evidence of Rhodes's eclectic tastes. The wooden comer posts on one of the staircases are carved in the form of the enigmatic soapstone eagles that were found at the Zimbabwe Ruins; Delft tiles decorate the downstairs skirtings and several of the fireplaces; and some of the fireplaces themselves have Zimbabwe soapstone surrounds and copper hoods.

Among the most interesting items are souvenirs from his travels, including various artefacts from the Zimbabwe Ruins, an exquisitely inlaid Moorish Egyptian travelling writing table, an old Cape stinkwood armoire with secret drawers and an elephant-shaped drinking cup.

There are very few paintings, and in any case, the vast areas of wood panelling don't encourage them. Ranged throughout the house, however, are a series of four rare 17th-century Flemish tapestries, these being allegorical depictions of America, Europe, Africa and Asia respectively.

Rhodes's books reflect his wide interests. The study houses a unique collection of obscure Roman and Greek classics. The library houses the bulk of the books, most of them dealing with travel and exploration.

When Rhodes was alive, two photographs of falcon statues - representing Ra, the ancient Egyptian sun-god - enjoyed pride of place next to his bed. These images were placed above and below a photograph of one of the soapstone eagles from the Zimbabwe Ruins - the juxtaposition of these images echoing Rhodes's belief that these two civilisations were connected in some way.

The bathroom adjoining Rhodes's bedroom is a highlight. It contains a huge bathtub carved from a single piece of Paarl mountain granite, for which the floor had to be specially reinforced. Water spurts through the mouth of a brass lion, and once the bath is full, it takes a mere five minutes before the water is stone cold again!

Rhodes enjoyed filling his house with people, and during his short residence at Grootte Schuur many visitors trooped through the heavy teak front door and took tea or partied on the colonnaded back veranda, his favourite place for entertaining.

Among the frequent guests were the Rudyard Kiplings, Lord and Lady Edward Cecil, Baden-Powell, the Duke of Westminster, and the treacherous Princess Radziwill who tried, in vain, to connive a permanent place for herself in Rhodes's bachelor life.

Many of Rhodes's esteemed guests were horrified at his egalitarian habit of throwing open his gates to the Cape Town public every weekend, where they would arrive, children in tow, to picnic happily on the lawns. Rhodes said: 'Some people like to have cows in their park; I like to have people in mine.'

The gardens at Groote Schuur enjoy a matchless setting against the hunched, benevolent presence of Devil's Peak. From the back veranda, shallow steps lead up past the formal terraces to an avenue of stone pines, from where one can gaze down at Baker's handiwork and the spread of urban Cape Town beyond.

The massive rose garden is edged with thick hedges of starry blue plumbago - Rhodes's favourite flower. The incredible esteem in which this controversial man was held is reflected in the fact that for many years after his death - 26 March 1902 - thousands of Capetonians would religiously commemorate the occasion by wearing a sprig of plumbago on their lapels.

Residence of Prime Ministers

For a long period (1911 to 1994) it was the official Cape residence of eleven Prime Ministers of South Africa.

Mr P.W. Botha and his wife Elize made Westbrooke the official residence from 1978-1989 when he was first Prime Minister (1978-1983) and then became President in (1983-1989). F.W. de Klerk decided to move back to Groote Schuur in his term in office and Nelson Mandela then moved back to Westbrooke (which he had renamed "Genadendal") after the 1994 election.

P.W. Botha was the first Prime Minister and then President to live in Westbrooke/Genadendal and make it the official residence of the Head of State. Nelson Mandela continued this practise and the Genadendal building again became the Cape Town residence of the South African President after 1994.

Visitors

Groote Schuur is now a museum and open to the public only by appointment or on occasional open days in aid of charity which are publicised in the press beforehand.

Where to Stay in Cape Town

Cape Town Accommodation options are numerous; with a large variety of different types spread throughout the Peninsula.

Cape Town Things to Do

Cape Town offers a myriad of other Museums as well as other Things to Do and places to see, whatever your tastes, inclinations or budget.