Rorke's Drift, situated 46 km southeast of Dundee on the Battlefields Route, is the site of one of the most famous battles of the Anglo-Zulu War.

The best-known drift through the Buffalo River, Rorke's Drift was named after James Rorke, a ferryman who drowned in its waters and whose remains lie buried at the foot of a nearby hillside. Looking at the unspoilt, majestic beauty of the surrounding countryside today, it's hard to imagine the bloody battles that once raged in the area.

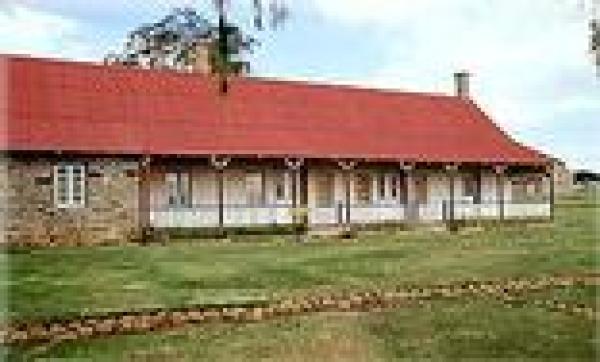

A mission station was established by the Reverend Otto Witt of the Swedish Missionary Society, who built a small church, mission house and cattle kraal at the foot of a rocky mountain 1 km west of Rorke's Drift. In honour of the King of Sweden, he called it Oscarsberg.

When Lord Chelmsford, the commander-in-chief of British forces in Natal, invaded Zululand at Rorke's Drift on 11 January 1879, he encamped on the other side of the river, 16km to the east, at Isandhlwana.

Being so conveniently located close by, the Swedish mission was promptly converted into a supply depot and hospital. On 22 January, the British were attacked by the Zulu chief, Cetshwayo - and were shocked by the extent of the Zulu resistance. They lost at least 850 of their own men and 470 black allies. The Zulus lost 1 000 soldiers.

After the battle, two regiments commanded by Dabulamanzi were sent to pursue men fleeing from Isandhlwana who crossed the river at what would later become known as Fugitive's Drift. The Zulu impis had received no order to attack Rorke's Drift.

Cetshwayo had apparently warned them that any attack into Natal would be futile. A force of impi swam the river, however, and were so heady with victory that they attacked the mission. Their king's warning, which they failed to heed, came terribly true.

At Rorke's Drift, a small force of just over 100 men - a mixed bag of flotsam and jetsam from the Victorian army - had been left under the command of Lt John Chard. Earlier, a column on its way to fight at Isandhlwana had left behind 300 Basuto troops to aid Lt Chard. When the Zulu attack on the mission station began, however, the Basuto and their European leader fled. Seeing the impi coming, Lt Chard prepared for battle as best he could.

A make shift fortress was made out of things such as sacks of mielies and biscuit boxes. The hospital bore the brunt of the attack, with most of the patients losing their lives. The others escaped to a central courtyard. The engagement raged until the following day, when finally an armed detachment under Lt-Col Russell arrived to relieve the defenders.

It turned out that the British had lost only 17 men in what became known as the battle of the 'Heroic Hundred', while the Zulus had lost 300. Both sides showed incredible valour. Eleven Victoria Crosses were awarded, and the bravery of Lt Chard is still commemorated by the SA Army with the John Chard Medal for bravery.

The main attractions at the Rorke's Drift Battle Museum are the magnificent model and audiovisual depictions of the battles that were fought in the region. In fact, the museum has attracted worldwide attention for its outstanding displays of the Anglo-Zulu War.

The countryside around Rorke's Drift is unspoilt and tranquil. You can see the natural grandeur that so many military artists have tried to capture on canvas. This is where you can savour the true majesty of a frontier landscape.

After the war, in 1882, the Swedish missionaries re-established themselves. In the last 30 years, the fame of Rorke's Drift as a battlefield has almost been matched by the fame of an arts and crafts centre run by the Evangelical Lutheran Church. In what started as a tiny workshop in 1962, black artists were initially trained by Swedish art teachers. Those who received their start here, include Azaria Mbatha, lino-cut artist John Muafangejo and sculptor Zuminkosi Zulu.

Many students of the centre from around the country have later won national and international acclaim, with their work being exhibited in galleries in Europe and North and South America. Many tapestries have been commissioned by well-known institutions, and hang in churches, offices and homes around the world.

The centre specialises in handwoven tapestries, pottery and silkscreen fabrics. The largest activity is weaving. The rugs and tapestries are made from pure karakul wool, which is handspun, dyed and woven into figurative or non-figurative designs. The designs have a wonderful clarity of colour and balance and, more importantly, not one of them is ever repeated - every work is unique.

The pottery consists of coiled and thrown pieces, ranging from the simplest to the most beautiful works of art. The potters use metal oxides for painting designs on the pots, which then receive a kaolin glaze. Designs are also sculpted or incised on the pots to give them their unique African pattern.

The potters, like the weavers and textile printers, are encouraged to develop their own originality.